The US stock rally continued unabated today, but bonds are flashing a warning signal.

Positive US-China trade and AI news sent the S&P 500, Nasdaq 100 and Dow Jones Industrial Average to fresh, all-time highs. However, a report that Amazon was set to cut 30,000 corporate jobs fueled a Treasury rally that highlights how the bond-market is increasingly priced for a US slowdown.

The overall tone is risk-on, simply because a number of favorable geopolitical and macro issues meant equities got bid as investors left havens like gold and silver and initially Treasuries, too. The positive backdrop ranged from US-China to Argentina on the geopolitical front to Qualcomm and Deutsche Telekom on the AI side. The overall message: Politics won’t get in the way of an AI investment cycle that continues apace and will keep economic and earnings growth in the US higher.

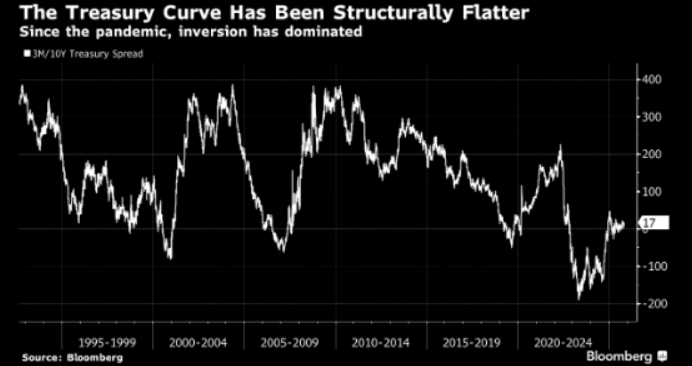

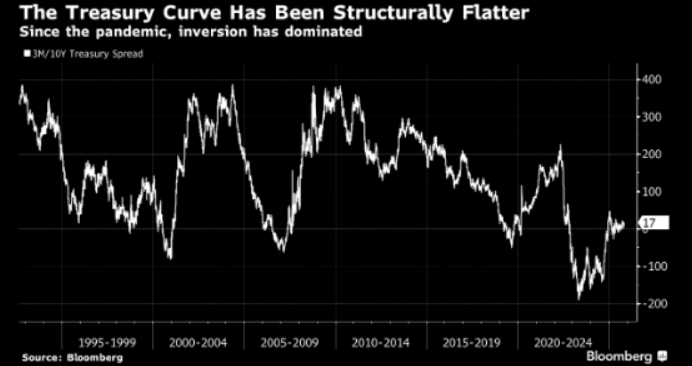

But if the outlook is all rainbows and so flowery, why is the 10-year Treasury yielding less than fed funds? One interpretation is that since the Federal Reserve’s last rate hike cycle, the central bank has countered with a structurally dovish policy path, cutting 125 basis points, soon to be 150, with CPI still at 3%, 1% above target. That has meant a flatter yield curve from 3 months to 30 years recently than at any time outside of recession before 2020.

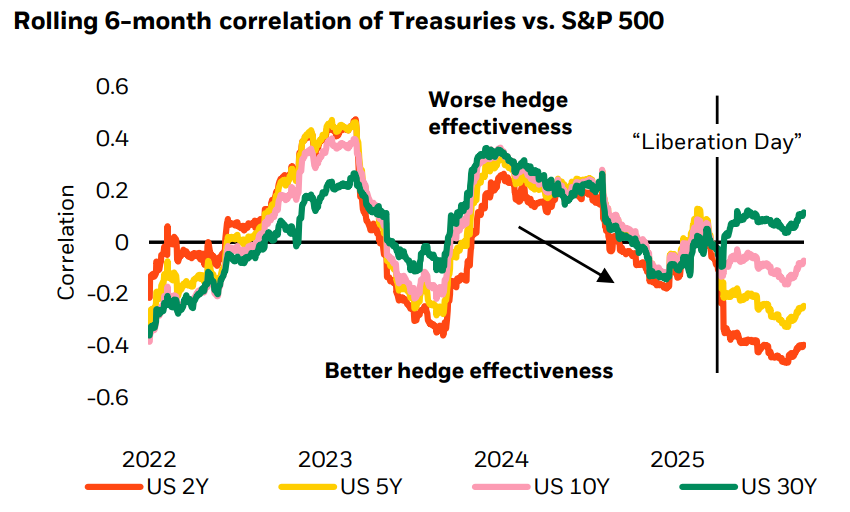

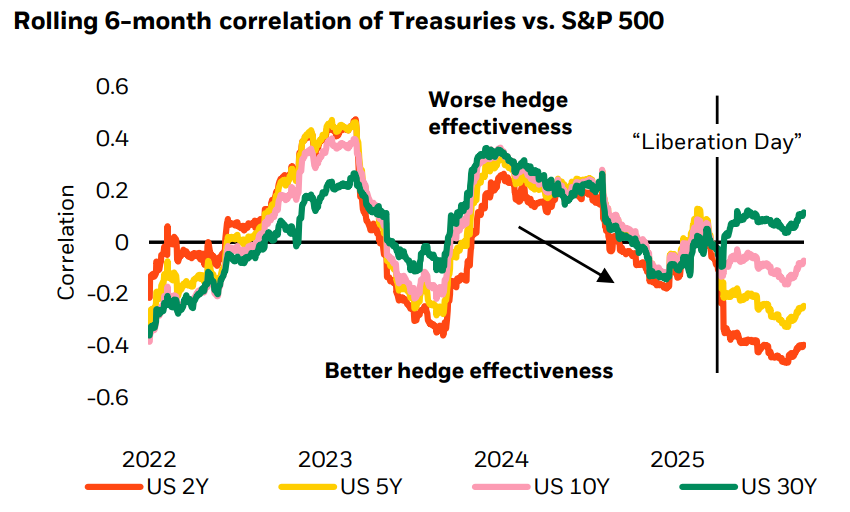

Another interpretation and not mutually-exclusive of the first is that the bond market is partially hedged for slowing, less so now than in 2023 or 2024 certainly. But we’ve come well off the curve steepening that climaxed early this year after the Trump administration unveiled an aggressive tariff policy. The fact that the Amazon news was met with a long-end Treasury rally taking the 10-year back below 4% speaks to that interpretation.

On an aggregate level, the U.S. economy continues to provide a solid growth backdrop, even with weakening labor market growth and still-elevated inflation that should continue to decline longer-term. What this backdrop masks, however, is the high level of dispersion embedded within the economy today. The fact is that many of the most resilient segments of the economy (be they corporations or households) are simply not terribly sensitive to elevated interest rates, as high levels of liquid assets and good cash flows make borrowing less necessary. At the same time, the lower 50% of America has far more non-mortgage debt than they do liquid assets. As such, when rates moved higher, they took on the stress from higher interest costs without benefitting from higher asset prices, or from the higher rate of return on cash. Meanwhile, they are also seeing weaker wage growth as the labor market comes under pressure. This pain, though, is largely masked in the aggregate numbers, as the lower 50% represents a more modest share of overall spending. Additionally, the interest rate-sensitive housing market remains structurally challenged, impacting much of the population today particularly the younger, low-to-medium income cohorts. It is for these reasons, and to support a labor market that has begun to display signs of weakness, that the Fed decided to cut policy rates at its mid-September meeting and why further cuts are likely in store in the months ahead. Moreover, while corporate sector leverage remains in good shape overall, this aggregate picture masks the greater interest rate sensitivity (reliance on credit) of smaller-to-medium-sized businesses, which are a significant source of new job creation.

If policy rates are likely heading lower in the shorter term, the Fed (and other global central banks) will also have to manage the possibility of anemic job growth due to technological and productivity gains in the medium term. Therefore, interest rate policy over the next decade could be quite different from a structural perspective than it was in the pre-Covid period. In fact, while the Fed previously struggled to elevate (the then-tame) inflation rate pre-Covid, we may transition to a place where the central bank struggles to elevate employment going forward. Some exposure to the long end part of the US bond market makes sense as rates may decline from currently high levels. We have bullish on 30yr UST since past few months as written in our below premium opinion piece on 4th Oct:

https://macro-spectrum.com/opinion/is-the-us-long-end-undervalued

Given the potential secular change and orientation of the Fed, these real rates further out the curve now deserve at least some thought.